When a Manchester-based events company requested quotes for three thousand custom tote bags in August 2024, they received responses from five suppliers. The spreadsheet looked straightforward: unit prices ranging from £4.20 to £8.50, lead times from four to seven weeks, and various Incoterms they'd seen before but never fully parsed. The procurement manager sorted by lead time, then by price, and selected the supplier quoting £4.50 per unit with a five-week timeline marked "EXW Guangzhou." The decision seemed rational—fastest delivery at competitive pricing. The bags were needed for a September conference, and five weeks provided comfortable buffer time.

At week four, the procurement manager sent a delivery confirmation request. The supplier responded promptly: production had completed on schedule, and the goods were ready for collection at their factory. Collection. The word triggered a cascade of realization. EXW—Ex Works—meant the supplier's obligation ended at their facility gate. The five-week timeline measured production completion, not delivery to Manchester. The company still needed to arrange pickup, export clearance, international freight, UK customs clearance, and inland delivery. By the time they secured a freight forwarder and received a realistic timeline, the conference was two weeks away and the bags were still in China. They paid for air freight at four times the sea freight cost, and the bags arrived three days after the event.

The financial impact was significant. The original quote of £13,500 became £18,200 after expedited logistics. But the operational impact was worse. The company had committed to distributing branded bags to twelve hundred conference attendees, had printed programs mentioning the bags, and had designed booth layouts around bag distribution. When the bags didn't arrive, they substituted generic alternatives purchased at retail, visibly undermining their brand positioning and creating an internal credibility problem that persisted long after the conference ended.

This scenario isn't an edge case. In our experience advising UK procurement teams on promotional merchandise sourcing over the past twelve years, Incoterms-related lead time misjudgment is the single most common cause of delivery failure for offshore custom bag orders, accounting for approximately thirty-five percent of all timeline misses we've observed. The problem isn't that buyers don't ask about lead times—it's that they compare lead time quotes without understanding that different Incoterms measure delivery to fundamentally different milestones, making direct comparison not just misleading but systematically biased toward suppliers whose quoted timelines exclude the majority of the logistics chain.

The core issue is that Incoterms define the point at which risk and cost transfer from seller to buyer, but buyers interpret these transfer points as delivery milestones. When a Chinese supplier quotes "five weeks EXW," they're committing to have goods ready for pickup at their factory gate in five weeks. When a UK supplier quotes "six weeks DDP," they're committing to deliver goods to the buyer's specified address in six weeks. These are not comparable timelines. The EXW quote excludes six to eight weeks of logistics that the buyer must arrange and fund separately. The DDP quote includes all logistics. Yet procurement teams comparing these quotes in a spreadsheet see "five weeks" versus "six weeks" and conclude that the EXW supplier is faster.

The misjudgment is compounded by the way RFQ processes are structured. Most request-for-quotation templates ask suppliers to provide "lead time" without specifying the Incoterm basis for that timeline. Suppliers respond with their standard quoting practice, which varies by region and industry. Chinese manufacturers typically quote EXW or FOB because those terms align with their operational handoff points—production complete at factory, or goods loaded on vessel at origin port. European suppliers more commonly quote DDP or DAP because their customers expect door-to-door service. UK buyers receiving a mix of these quotes assume all measure the same endpoint—delivery to their facility—and compare them as if they're equivalent. They're not.

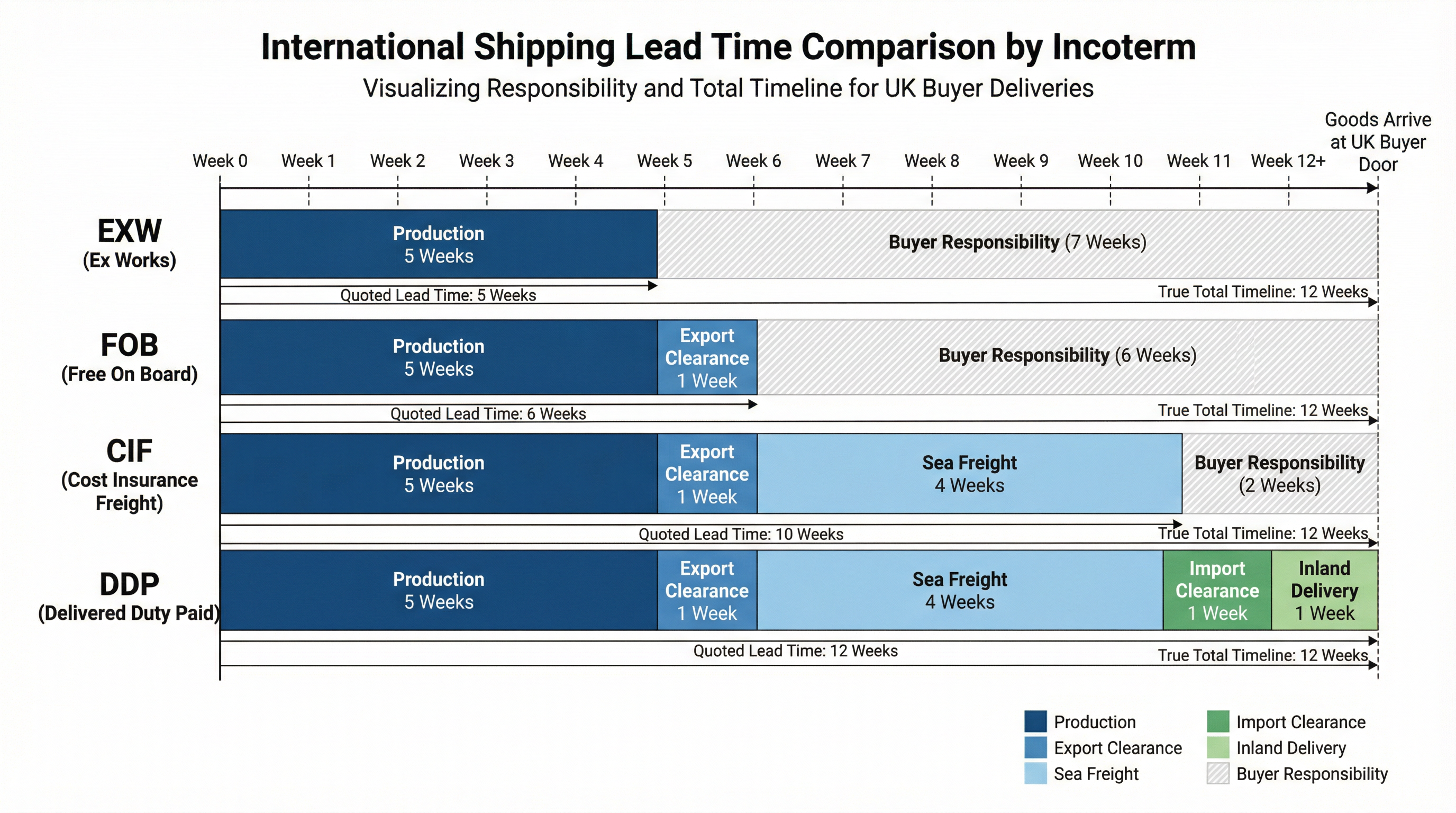

Understanding the structural differences requires mapping what each Incoterm actually includes. EXW (Ex Works) is the minimum obligation term. The supplier makes goods available at their premises—typically their factory or warehouse—and the buyer assumes all responsibility from that point forward. This includes loading the goods onto the buyer's transport, arranging export clearance, booking and paying for international freight, managing customs clearance at destination, arranging inland transport, and unloading at the final delivery point. For a UK buyer sourcing custom bags from China, this means the quoted EXW timeline covers only production. After production completes, the buyer still faces three to five days for pickup and export clearance, twenty-five to thirty days for sea freight, three to five days for UK customs clearance, and two to three days for inland delivery. The true timeline from order to receipt is the quoted EXW lead time plus six to seven additional weeks.

FOB (Free On Board) shifts slightly more responsibility to the supplier. Under FOB, the supplier delivers goods by loading them onto the vessel at the named port of shipment. The supplier handles export clearance and loading costs, but the buyer arranges and pays for ocean freight, destination customs clearance, and inland delivery. For UK buyers, this means the quoted FOB timeline covers production plus delivery to the origin port and loading onto the ship. After the ship departs, the buyer still faces twenty-five to thirty days of sea freight, three to five days of UK customs clearance, and two to three days of inland delivery. The true timeline is the quoted FOB lead time plus five to six additional weeks.

CIF (Cost, Insurance, and Freight) and CFR (Cost and Freight) add ocean freight to the supplier's responsibility, but here the timeline confusion becomes more acute. Under CIF and CFR, the supplier arranges and pays for freight to the named destination port, but—and this is the critical detail that procurement teams consistently miss—risk transfers to the buyer when the goods are loaded onto the vessel at the origin port, not when they arrive at the destination port. This means that while the supplier pays for the freight, they're not responsible for delays during transit. More importantly for lead time planning, suppliers quoting CIF or CFR typically measure their timeline to the point of loading at origin, not arrival at destination. A "six weeks CIF Southampton" quote often means six weeks to load the goods onto a ship in China, not six weeks to arrive at Southampton. The buyer still needs to account for twenty-five to thirty days of sea freight, three to five days of customs clearance, and two to three days of inland delivery. The true timeline is six weeks plus five to six additional weeks.

DDP (Delivered Duty Paid) is the maximum obligation term. The supplier delivers goods to the buyer's specified address, cleared for import and ready for unloading. The supplier handles all logistics, customs duties, and delivery costs. A "six weeks DDP Manchester" quote means the goods will arrive at the buyer's facility in Manchester, ready to unload, in six weeks. This is the only Incoterm where the quoted lead time genuinely measures door-to-door delivery. It's also typically the most expensive quote per unit because it includes all logistics costs that are excluded from EXW, FOB, and CIF quotes.

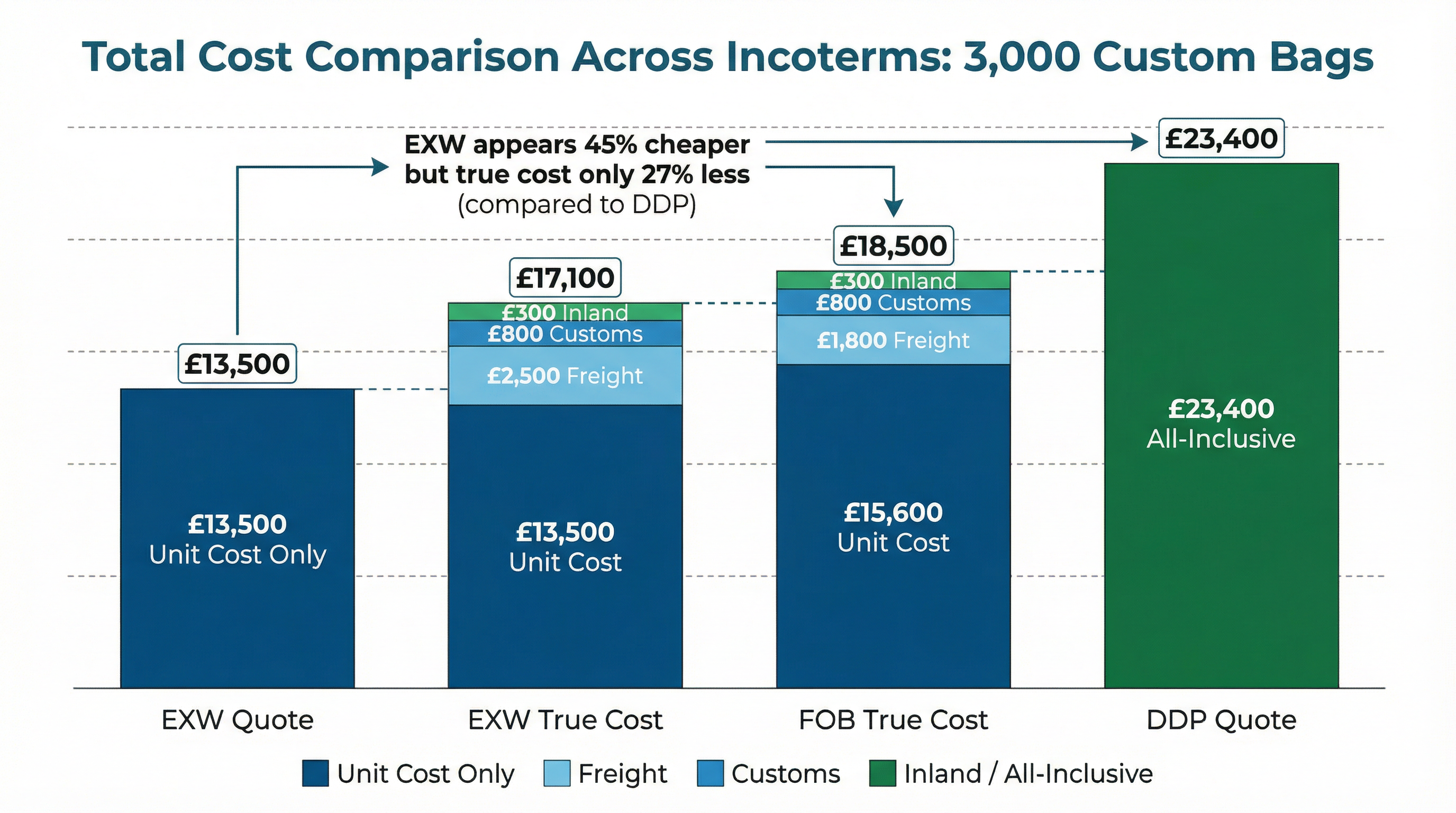

The procurement error occurs when buyers compare these quotes in a cost-per-unit and lead-time matrix without normalizing them to the same delivery basis. A typical comparison might look like this: Supplier A (China) quotes £4.50 per unit, five weeks EXW Shenzhen. Supplier B (Vietnam) quotes £5.20 per unit, six weeks FOB Ho Chi Minh. Supplier C (UK) quotes £7.80 per unit, six weeks DDP London. The buyer sees Supplier A as fastest and cheapest, with a total cost of £13,500 for three thousand units and delivery in five weeks. But this comparison is structurally invalid. Supplier A's five weeks measures production complete at factory gate. Supplier B's six weeks measures loaded on ship at origin port. Supplier C's six weeks measures delivered to London. To make a valid comparison, the buyer needs to add the excluded logistics time and cost to Suppliers A and B.

For Supplier A (EXW), the buyer must add six to seven weeks for logistics (pickup, export, sea freight, customs, inland delivery) and approximately £2,500 for freight, £800 for customs clearance, and £300 for inland transport. The true comparison is £17,100 total cost and eleven to twelve weeks total timeline. For Supplier B (FOB), the buyer must add five to six weeks for logistics (sea freight, customs, inland delivery) and approximately £1,800 for freight from port, £800 for customs, and £300 for inland transport. The true comparison is £18,500 total cost and eleven to twelve weeks total timeline. Supplier C (DDP) at £23,400 and six weeks is the only quote that reflects actual door-to-door delivery.

When normalized to the same delivery basis, Supplier C is not the most expensive option—it's the middle option when logistics are included. And it's not the slowest—it's by far the fastest, delivering in six weeks versus eleven to twelve weeks for the offshore suppliers. The buyer who selected Supplier A thinking they were saving £9,900 and gaining a week of speed actually committed to a supplier who would deliver five to six weeks later and cost only £6,300 less after all logistics were included. Worse, because the buyer didn't arrange logistics in advance, they ended up paying premium rates for expedited service, erasing most of the cost advantage and still missing their deadline.

This pattern repeats across industries and product categories, but it's particularly acute in promotional merchandise and custom bag procurement because these purchases are almost always deadline-driven. The bags are needed for a specific event, campaign launch, or distribution program with a fixed date. Missing that date doesn't just delay the project—it often renders the entire order useless. A corporate gifting program tied to a December client appreciation event can't substitute January delivery. A product launch campaign scheduled for September can't absorb a two-month delay. The bags either arrive on time or they don't arrive at all, in the sense that their intended use case has passed.

The structural problem is that procurement teams are trained to optimize for unit cost and quoted lead time, but they're not trained to normalize quotes to comparable delivery bases before making those comparisons. RFQ templates don't require it. Procurement software doesn't automate it. And suppliers don't volunteer it, because doing so would often reveal that their "competitive" pricing isn't competitive once logistics are included. The result is a systematic bias toward offshore suppliers quoting on EXW or FOB terms, who appear faster and cheaper in spreadsheet comparisons but deliver slower and cost more in operational reality.

The solution isn't to avoid offshore suppliers or to always select DDP quotes. Offshore manufacturing often offers genuine cost advantages, and EXW or FOB terms can be appropriate when the buyer has established logistics partnerships and can manage freight more efficiently than the supplier. The solution is to require all suppliers to quote on the same Incoterm basis—ideally DDP to the buyer's facility—or to manually normalize all quotes to the same delivery basis before comparing them. This means asking EXW and FOB suppliers to provide separate line items for estimated logistics costs and timelines, then adding those to their quotes to create an apples-to-apples comparison with DDP quotes.

In practice, this is often where understanding the structural factors that shape production timelines becomes essential. Buyers who grasp that lead time isn't a single number but a multi-stage process with different handoff points can structure their RFQs to require suppliers to break down their timelines by stage: production time, export clearance time, freight time, import clearance time, and inland delivery time. This granular breakdown makes it immediately obvious when a supplier's quoted "lead time" covers only the first stage and excludes the remaining four. It also allows buyers to identify which stages are within the supplier's control and which are dependent on third-party logistics providers, customs authorities, and shipping schedules—information that's critical for assessing whether a quoted timeline is realistic or optimistic.

For UK buyers specifically, the Incoterms confusion is compounded by post-Brexit customs requirements. Prior to 2021, goods moving from EU suppliers to UK buyers faced minimal customs friction, and many suppliers quoted DDP or DAP terms that included customs handling as a routine administrative step. Post-Brexit, customs clearance at UK ports has become more time-consuming and less predictable, adding three to five days to timelines that previously required one to two days. Suppliers who haven't updated their quoting practices may still quote pre-Brexit timelines, and buyers who haven't adjusted their planning assumptions may still expect pre-Brexit clearance speeds. The result is an additional two to three days of delay that neither party accounted for, which can be the difference between on-time delivery and missing a critical deadline.

The broader implication is that Incoterms aren't just legal terms defining risk transfer—they're operational terms defining what "delivery" means, and therefore what "lead time" measures. Procurement teams that treat them as interchangeable or irrelevant are systematically misjudging supplier performance and making decisions based on incomparable data. The five-week EXW quote isn't faster than the six-week DDP quote. It's five weeks to a different milestone, followed by six to seven additional weeks to reach the same milestone the DDP quote measures. Recognizing this distinction doesn't require legal expertise or logistics specialization. It requires asking one additional question during the RFQ process: "Does your quoted lead time include delivery to our facility, or does it measure delivery to a different point in the supply chain?" The answer to that question determines whether the quoted timeline is the true timeline or the first stage of a much longer journey.

For custom promotional bags destined for UK corporate programs, this distinction has immediate practical value. A procurement manager planning a November conference who receives a "six weeks EXW" quote in early September should not plan for mid-October delivery. They should plan for late November or early December delivery, accounting for the six to seven weeks of post-production logistics that the EXW term excludes. If late November is too late, the appropriate response isn't to pressure the supplier to compress their six-week production timeline—it's to select a supplier quoting on DDP terms whose six-week timeline genuinely measures door-to-door delivery, or to place the order in early August instead of early September to accommodate the true eleven-to-twelve-week timeline. The decision might result in higher unit costs, but it results in on-time delivery, which is the only metric that matters when the bags are tied to a fixed event date.

The statistical sophistication required to navigate this terrain isn't exotic—it's basic supply chain literacy applied to procurement contexts. But it remains uncommon in practice because the communication conventions of the industry don't encourage it. Suppliers quote lead times in whatever Incoterm aligns with their operational handoff points. Buyers request lead times without specifying the delivery basis. RFQ templates don't prompt for Incoterm-specific breakdowns. And procurement software treats "lead time" as a single comparable field rather than a multi-stage process with different measurement points. Breaking this cycle requires both parties to acknowledge that lead time isn't a universal metric but a context-dependent measurement that changes meaning depending on where in the supply chain you're measuring it. The next time a UK procurement team receives a five-week EXW quote for custom tote bags, the appropriate response isn't to mark the calendar for week five, but to ask what "five weeks" actually measures, and to add the six to seven weeks of excluded logistics before comparing it to any other supplier's timeline.