The moment a client approves a sample, there is a palpable shift in the conversation. The tone changes from exploratory to transactional. Delivery dates are proposed. Purchase orders are drafted. Internal stakeholders are notified that the project is "greenlit." From the factory floor perspective, this is precisely when the most consequential misjudgments begin to accumulate.

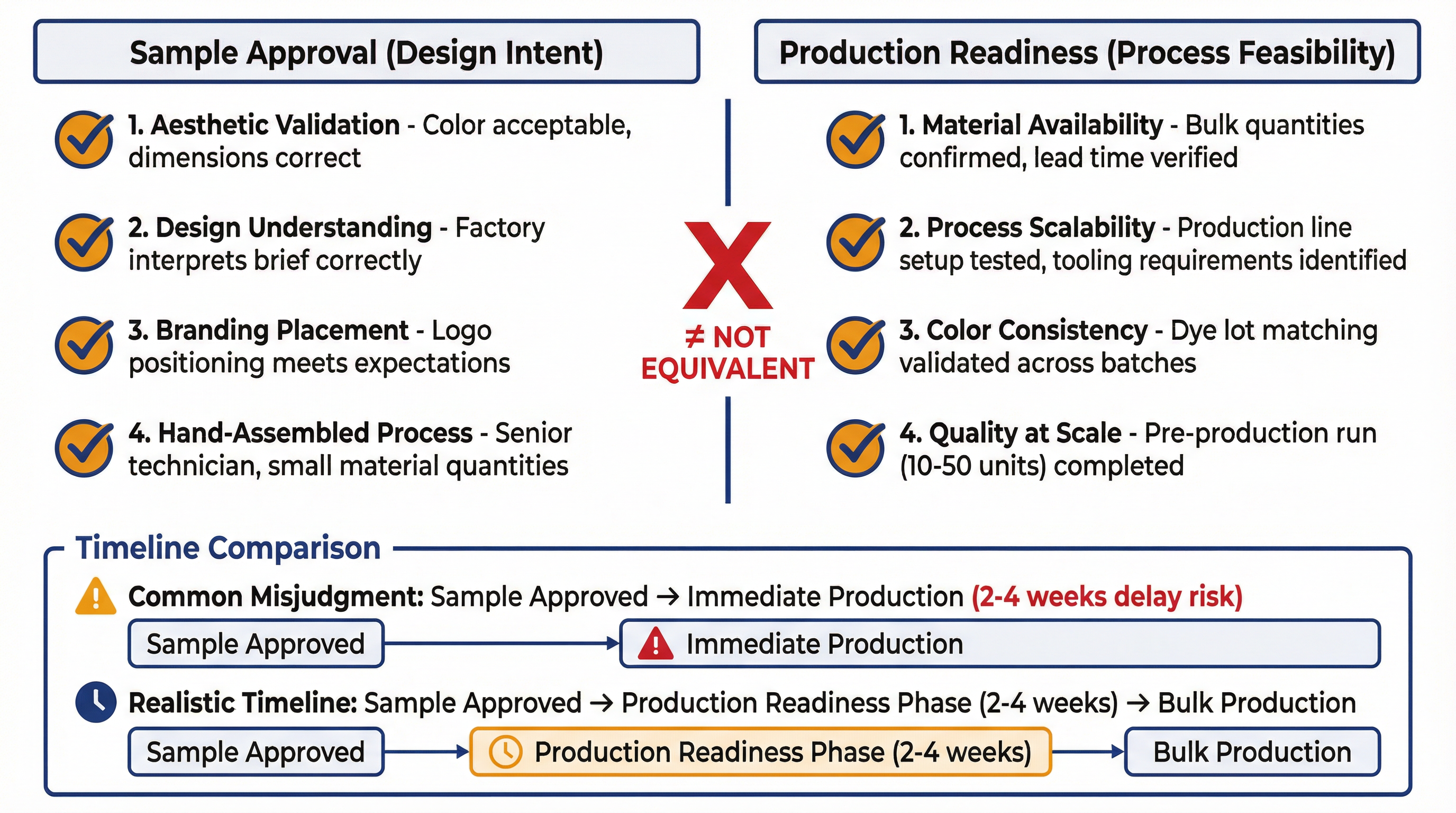

Sample approval confirms that the design intent has been understood. The colour is acceptable. The dimensions meet expectations. The branding placement aligns with the brief. These are meaningful validations, but they address only one dimension of what determines whether a custom bag order can proceed to production without delay. What sample approval does not confirm—and what procurement teams frequently assume it does—is whether the production process itself is ready to replicate that sample at scale, within the required timeline, using materials that are actually available in the quantities needed.

The distinction matters because samples and bulk production operate under fundamentally different constraints. A sample is typically assembled by hand, often by a senior technician who has direct access to the full range of materials in the factory's inventory. If a particular shade of lining fabric is needed, a small cut can be taken from an existing roll, even if that roll is earmarked for another client's order. If a zipper needs to be a specific length, it can be trimmed manually. If a logo needs to be positioned with millimetre precision, the technician can adjust the placement by eye. These accommodations are not only possible during sampling—they are expected. The sample's purpose is to validate design intent, not to demonstrate production efficiency.

Bulk production, by contrast, is a choreographed sequence of steps that depend on material availability, machine setup, and process consistency. The lining fabric that was "borrowed" for the sample may not exist in the 500-metre quantities required for a 2,000-unit order. The zipper that was hand-trimmed cannot be replicated that way across thousands of bags without introducing unacceptable variation. The logo placement that looked perfect on the sample may require custom tooling or jig adjustments when transferred to a production line where speed and repeatability are prioritised over manual precision.

This is where the timeline compression begins. A procurement team approves the sample on Monday and requests a delivery date. The factory's production planner reviews the order and identifies that the lining fabric used in the sample is not currently stocked in bulk. The lead time to procure it is three weeks. The client, however, has already communicated internally that the sample was "approved" and expects production to commence immediately. When the factory explains the material lead time, the response is often some variation of: "But you already made the sample. Why can't you just make more?"

The question reveals the core misjudgment. The sample was made using materials that were available in small quantities. Bulk production requires materials that are available in large quantities, often from specific suppliers who can guarantee consistency across multiple production runs. If the lining fabric in the sample came from Supplier A, but Supplier A cannot deliver 500 metres within the required timeframe, the factory must either delay production or source an alternative from Supplier B. If Supplier B's fabric is even slightly different in weight, texture, or dye lot, the bulk production will not match the approved sample. The client will reject it during quality inspection, and the entire timeline resets.

Experienced project managers recognise this pattern and attempt to surface it during the sample approval phase. They ask: "Is this lining fabric available in bulk?" "Can this zipper be sourced in the quantities we need?" "Does this logo application method scale to production volumes?" These questions are not administrative formalities. They are attempts to identify whether the approved sample represents a production-ready design or merely a design-intent prototype that will require further iteration once material and process constraints are factored in.

The challenge is that these questions often go unanswered, or are answered with assumptions rather than verified data. A procurement manager may respond: "The lining looks fine. Just use whatever you have in stock." This instruction, while pragmatic in intent, introduces a new variable. If the factory substitutes a different lining fabric to meet the timeline, the bulk production will not match the approved sample. If the factory insists on sourcing the exact lining fabric from the sample, the timeline extends by however long that procurement takes. Neither outcome aligns with the client's expectation that sample approval means "production can begin immediately."

The same dynamic applies to colour matching. A sample may use a custom-dyed fabric that was produced in a small batch specifically for prototyping. Replicating that colour at scale requires either ordering a new dye lot from the same supplier—which introduces lead time—or accepting a "close match" from existing inventory, which introduces variation. Clients who approve samples without specifying whether exact colour matching is mandatory or whether a tolerance range is acceptable leave the factory in a position where any decision will be wrong. If the factory proceeds with a close match, the client may reject it as "not what we approved." If the factory delays to source an exact match, the client may complain about timeline slippage.

Process validation introduces another layer of complexity that sample approval does not address. A sample bag may have reinforced stitching at stress points—handles, corners, zipper ends—that was applied manually by the technician. Replicating that reinforcement on a production line requires either programming the sewing machines to execute the same stitch pattern automatically, or training production staff to apply it consistently by hand. The former requires setup time and may reveal that the stitch pattern is not compatible with the machine's capabilities. The latter introduces variability and slows throughput. Neither scenario was tested during the sample phase, because the sample was not produced under production conditions.

This is not a failure of the sampling process. Samples are meant to validate design intent, and they do that effectively. The failure occurs when procurement teams conflate design intent validation with production readiness validation. The former confirms that the design is desirable. The latter confirms that the design can be manufactured at scale, within the required timeline, using materials and processes that are actually available. These are distinct milestones, and treating them as equivalent systematically compresses the timeline in ways that become difficult to recover.

The practical consequence is that orders which appear to be "ready for production" immediately after sample approval often require an additional two to four weeks of material sourcing, process validation, and pre-production setup before bulk manufacturing can actually begin. Clients who build their delivery timelines based on the assumption that production starts the day after sample approval find themselves facing delays that feel arbitrary but are in fact structural. The factory is not being slow. The factory is executing the steps that were not accounted for when the timeline was originally estimated.

Organisations that maintain reliable timelines tend to treat sample approval as the beginning of the production readiness phase, not the end of it. They use the approved sample as a reference point to verify material availability, confirm process feasibility, and identify any tooling or setup requirements that were not apparent during the sampling phase. They ask the factory to produce a small pre-production run—typically 10 to 50 units—using the same materials, machines, and processes that will be used for bulk production. This run surfaces issues that the sample did not reveal: colour variation between dye lots, stitching inconsistencies at production speed, structural weaknesses that only appear when bags are assembled in volume.

This approach adds time to the front end of the project, but it prevents the far more costly delays that occur when bulk production reveals problems that could have been identified earlier. A pre-production run that takes two weeks and identifies a material sourcing issue is vastly preferable to a bulk production run that takes four weeks, passes quality inspection, and then gets rejected by the client because the lining fabric does not match the approved sample.

The broader implication is that custom bag orders require a more nuanced understanding of what different milestones actually validate. Design approval confirms aesthetic intent. Sample approval confirms that the factory understands the design. Material confirmation validates that the required inputs are available in the necessary quantities. Process validation confirms that the production line can replicate the sample consistently. Quality inspection verifies that the output meets specifications. These are sequential dependencies, not parallel activities. Treating sample approval as if it encompasses all of these validations creates a false sense of readiness that collapses under the weight of actual production constraints.

For procurement teams working within fixed timelines, the key decision point is not whether to approve the sample, but whether to commit to a delivery date before the production readiness phase is complete. Understanding how these validation stages fit within the broader timeline is essential for organisations managing the full scope of bringing a custom bag design to market. Approving a sample and immediately locking in a delivery schedule assumes that no material, process, or tooling issues will emerge. That assumption is occasionally correct, particularly for simple designs using standard materials. For custom bags with specific colour requirements, non-standard components, or structural features that deviate from the factory's typical product range, the assumption is rarely correct. The timeline compression that results is not a manufacturing failure. It is a planning failure that originates in the conflation of design approval with production readiness.

The path forward is not to slow down sample approval, but to recognise it for what it is: confirmation that the design is understood and acceptable. Production readiness is a separate milestone that requires separate validation. Clients who understand the process that shapes delivery timelines build that validation phase into their schedules. Clients who do not find themselves managing delays that could have been anticipated, had the distinction between design intent and production feasibility been recognised earlier.