There is a particular kind of disappointment that occurs when a procurement team receives their first bulk shipment of custom bags and discovers that the quality does not match the sample they approved three months earlier. The stitching is slightly looser. The handles sit at a marginally different angle. The fabric feels subtly different to the touch. Nothing is technically defective, yet nothing feels quite right either.

The instinct is to assume something went wrong during production. Perhaps the factory cut corners. Perhaps quality control failed. Perhaps the supplier substituted inferior materials. These explanations feel logical because they preserve the assumption that the approved sample represented a reliable preview of what bulk production would deliver.

In practice, this assumption is where quality expectations in custom bag procurement begin to diverge from manufacturing reality.

The pre-production sample that procurement teams approve is not a miniature version of the bulk order. It is a fundamentally different product, made under fundamentally different conditions, by a fundamentally different process. Understanding this distinction does not excuse genuine quality failures, but it does explain why expecting sample-identical bulk output represents a category error in how manufacturing actually works.

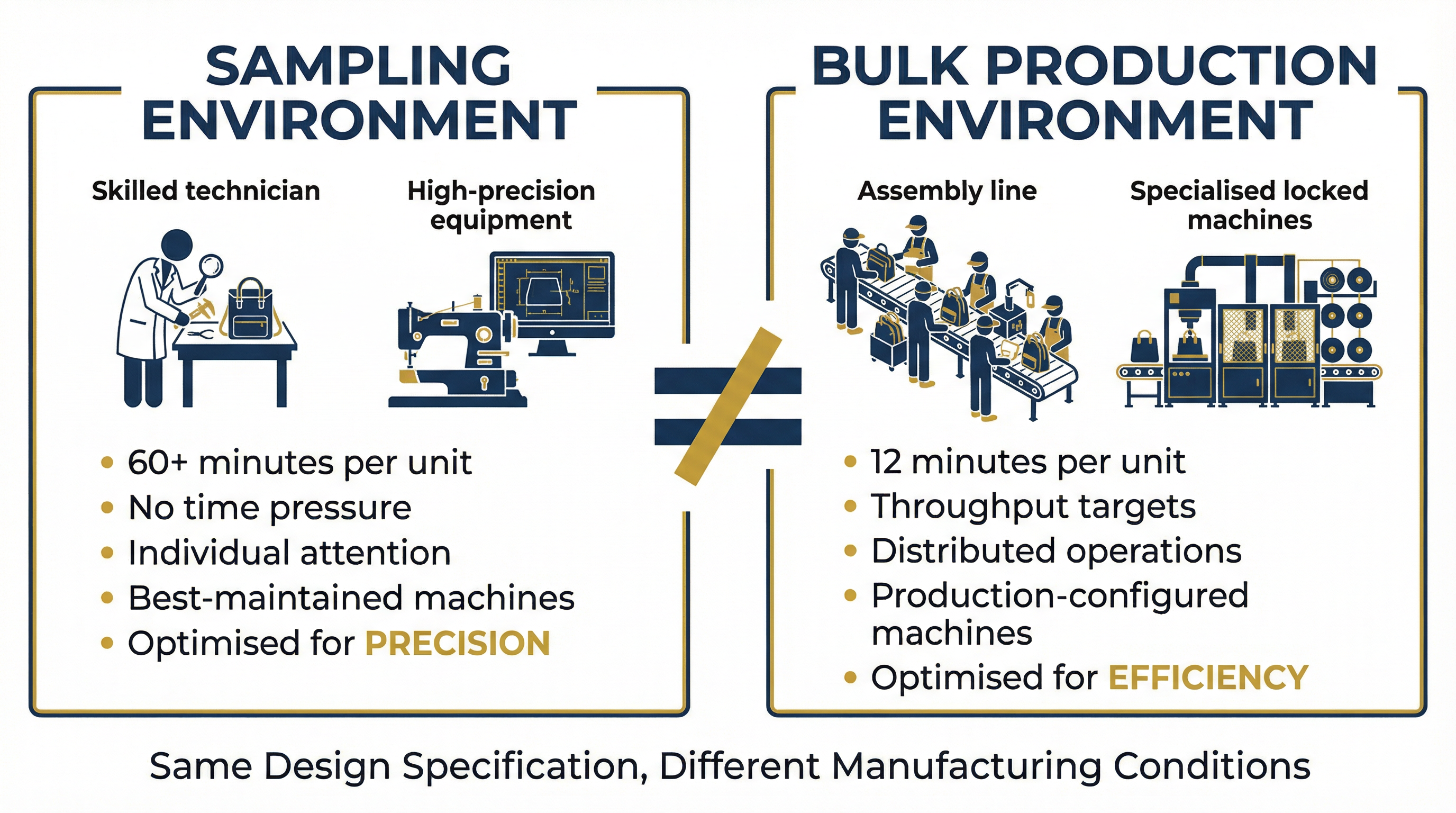

When a factory produces a pre-production sample for a custom tote bag or promotional holdall, that sample is typically made in a dedicated sampling department. This department operates under conditions that bear little resemblance to the production floor where bulk orders are manufactured. The sampling team consists of highly skilled technicians whose primary job is to interpret design specifications and produce a physical representation of what the buyer wants. They work without time pressure. They have access to the best-maintained equipment. They can spend sixty minutes or more on a single unit that will eventually be produced in twelve minutes during bulk manufacturing.

The sampling environment is optimised for precision, not efficiency. When a sampling technician encounters an ambiguity in the tech pack, they can pause, consult with colleagues, and make a considered decision about how to proceed. When a stitch line does not sit perfectly, they can unpick it and try again. When the fabric behaves unexpectedly, they can adjust their technique in real time. Every decision point receives individual attention.

Bulk production operates under entirely different constraints. The production floor is optimised for throughput, consistency, and cost efficiency. Workers are assigned to specific operations within a larger assembly sequence. The person who attaches handles may never see the person who finishes the edges. Each operator performs their assigned task hundreds of times per day, developing muscle memory that enables speed but also creates patterns that differ from the sampling technician's approach.

The machines themselves are different. Sampling departments often use versatile equipment that can be reconfigured for different stitch types and material weights. Production lines use specialised machines locked into specific configurations for maximum efficiency. A sampling machine might be adjusted three times during the creation of a single sample. A production machine might run unchanged for an entire shift, producing thousands of identical operations.

This is not a criticism of manufacturing practice. It is a description of how manufacturing economics work. The efficiency gains that make bulk production affordable require standardisation that sampling does not. The flexibility that makes sampling accurate requires time investment that bulk production cannot sustain.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that the approved sample represents a best-case interpretation of the design specification, produced under conditions that cannot be replicated at scale. The bulk order will be produced under conditions optimised for different objectives. Both approaches are legitimate. Neither is wrong. But they produce different results.

What this means for quality expectations is that procurement teams should evaluate samples not as previews of bulk output, but as demonstrations of design feasibility. The sample proves that the design can be manufactured. It establishes the target that production will aim toward. It does not guarantee that every unit in a ten-thousand-piece order will match the sample exactly.

Professional procurement practice accounts for this reality through tolerance specifications. Rather than expecting sample-identical output, experienced buyers define acceptable variation ranges for critical characteristics. Handle attachment position might be specified as plus or minus three millimetres from the sample. Colour consistency might be defined within a Delta E range. Stitch density might be acceptable within a specified stitches-per-inch tolerance.

These tolerance specifications acknowledge that bulk production introduces variation that sampling does not. They transform quality assessment from a subjective comparison against a single sample into an objective measurement against defined parameters. They also provide factories with clear targets that can be monitored and maintained throughout production.

The challenge for procurement teams new to custom bag sourcing is that tolerance specification requires understanding which characteristics matter and what variation ranges are achievable. This understanding develops through experience with manufacturing processes and materials. Recognising how sample approval fits within the broader stages of custom bag production helps procurement teams approach quality expectations with appropriate calibration.

There is also a timing dimension to the sample-bulk quality relationship that procurement teams often overlook. The sample approved in month one may have been produced using fabric from a specific mill batch. The bulk order produced in month four may use fabric from a different batch, sourced from the same mill but manufactured under different conditions. Both batches meet the same specification. Both are technically correct. But they are not identical.

This batch variation compounds across every material in the bag. The thread, the hardware, the lining, the reinforcement materials—each component introduces its own variation range. When these variations combine across thousands of units, the aggregate effect can produce output that feels different from the sample even when every individual component meets specification.

The most effective approach to managing this reality is to establish quality expectations before sample approval rather than after bulk delivery. This means defining tolerance ranges during the specification phase, not during the inspection phase. It means understanding that sample approval validates design intent, not production output. It means recognising that the sample and the bulk order are related but distinct products.

None of this excuses genuine quality failures. When bulk production deviates beyond acceptable tolerances, when materials are substituted without approval, when workmanship falls below professional standards—these are legitimate quality issues that require correction. The point is not that quality does not matter. The point is that quality assessment requires appropriate benchmarks.

The pre-production sample is a valuable tool for validating design feasibility and establishing visual reference points. It is not a guarantee that bulk production will produce identical output. Understanding this distinction helps procurement teams set appropriate expectations, define meaningful quality parameters, and evaluate bulk deliveries against achievable standards rather than idealised assumptions.

For organisations managing custom bag procurement for UK corporate gifting programmes, this understanding becomes particularly important when working with offshore manufacturing partners. The physical and temporal distance between sample approval and bulk delivery creates opportunities for expectation misalignment that domestic procurement does not face. Establishing clear tolerance specifications and quality parameters before production begins reduces the risk of disappointment when bulk shipments arrive.

The sample isolation phenomenon is not a flaw in manufacturing practice. It is a structural feature of how production economics work. Procurement teams that understand this feature can work with it rather than against it, setting expectations that align with manufacturing reality and defining quality standards that production can consistently achieve.

The practical mechanics of this isolation become clearer when examining specific production scenarios. Consider a custom cotton tote bag with screen-printed branding. During sampling, the printing technician can position each bag individually under the screen, ensuring perfect alignment. During bulk production, bags move through an automated or semi-automated printing line where positioning tolerance is measured in millimetres rather than perfection. The sample print sits exactly where the design specified. The bulk prints sit within an acceptable range of that specification.

This positional variation is not a defect. It is a characteristic of volume production. The question is not whether variation exists, but whether the variation falls within acceptable parameters. Professional procurement practice defines these parameters in advance, transforming quality assessment from subjective disappointment into objective measurement.

The fabric itself behaves differently at scale. Sampling typically uses fabric cut from the centre of a roll, where consistency is highest. Bulk production uses fabric from across entire rolls, including edge sections where tension variation during weaving or knitting can affect hand feel and drape. Both sections meet the same specification. Both are technically correct. But they feel different when handled.

Temperature and humidity variations across production days also affect output consistency. A bag produced on a humid Monday morning may have slightly different characteristics than one produced on a dry Thursday afternoon. These environmental factors are controlled within ranges, not eliminated entirely. The sample was produced under specific environmental conditions that cannot be replicated across weeks of bulk production.

Worker skill distribution adds another dimension of variation. The sampling technician who produced the approved sample may be the most experienced person in the factory. Bulk production distributes work across teams with varying skill levels. Quality control processes catch output that falls outside acceptable ranges, but they do not transform every worker into the sampling technician.

Understanding these mechanics helps procurement teams ask better questions during the specification phase. Rather than asking whether bulk production will match the sample, experienced buyers ask what tolerance ranges the factory can consistently achieve. Rather than assuming sample quality represents production capability, they request information about production line configurations and quality control processes.

The most sophisticated procurement operations treat sample approval and production specification as related but distinct activities. Sample approval validates that the design can be manufactured and establishes visual reference points. Production specification defines the parameters within which bulk manufacturing will operate. Both activities are necessary. Neither replaces the other.

This dual-track approach requires more upfront investment in specification development. It requires procurement teams to understand manufacturing processes well enough to define meaningful tolerance ranges. It requires communication with suppliers about production capabilities and limitations. But it produces better outcomes than the alternative: approving a sample, assuming bulk production will match it, and experiencing disappointment when manufacturing reality asserts itself.

The sample isolation phenomenon also has implications for supplier selection. Factories that produce excellent samples may or may not produce excellent bulk output. The skills and processes that enable precise sampling are different from those that enable consistent bulk production. Evaluating suppliers requires assessing both capabilities, not assuming that one predicts the other.

Some factories excel at sampling because they invest heavily in their sampling departments, using them as sales tools to win orders. Their production capabilities may be less developed. Other factories produce adequate samples but excel at bulk production, maintaining consistency across large orders through well-developed quality systems. Neither profile is inherently better. But procurement teams benefit from understanding which profile they are working with.

The timeline between sample approval and bulk delivery creates additional complexity. Market conditions change. Material availability shifts. Factory capacity fluctuates. The production environment that existed when the sample was approved may not exist when bulk manufacturing begins. These changes do not necessarily affect quality, but they can affect the relationship between sample and bulk output.

For UK procurement teams sourcing custom bags for corporate gifting programmes, these considerations become particularly relevant during peak ordering seasons. Factories operating at capacity may have less flexibility to accommodate special requests or maintain the attention levels that sampling received. Understanding this dynamic helps procurement teams plan timelines that account for production realities rather than assuming consistent capability regardless of timing.

The fundamental insight is that pre-production samples and bulk orders are different products made by different processes for different purposes. The sample demonstrates what is possible. The bulk order demonstrates what is achievable at scale. Both have value. Neither guarantees the other.

Procurement teams that internalise this distinction approach quality management with appropriate expectations. They define tolerance ranges rather than expecting perfection. They assess bulk output against achievable standards rather than idealised samples. They work with manufacturing reality rather than against it.

This is not a lowering of standards. It is a calibration of expectations to match manufacturing physics. The goal remains high-quality output that serves its intended purpose. The method acknowledges that achieving this goal at scale requires different approaches than achieving it in sampling.