There is a persistent assumption in B2B procurement that payment terms exist purely as a financial arrangement between buyer and supplier. The buyer negotiates for extended terms to preserve working capital. The supplier accepts terms that balance cash flow needs against the desire to secure the order. Both parties treat this as a commercial negotiation separate from the operational aspects of production. This framing is incomplete, and the incompleteness creates friction that many procurement teams never fully understand.

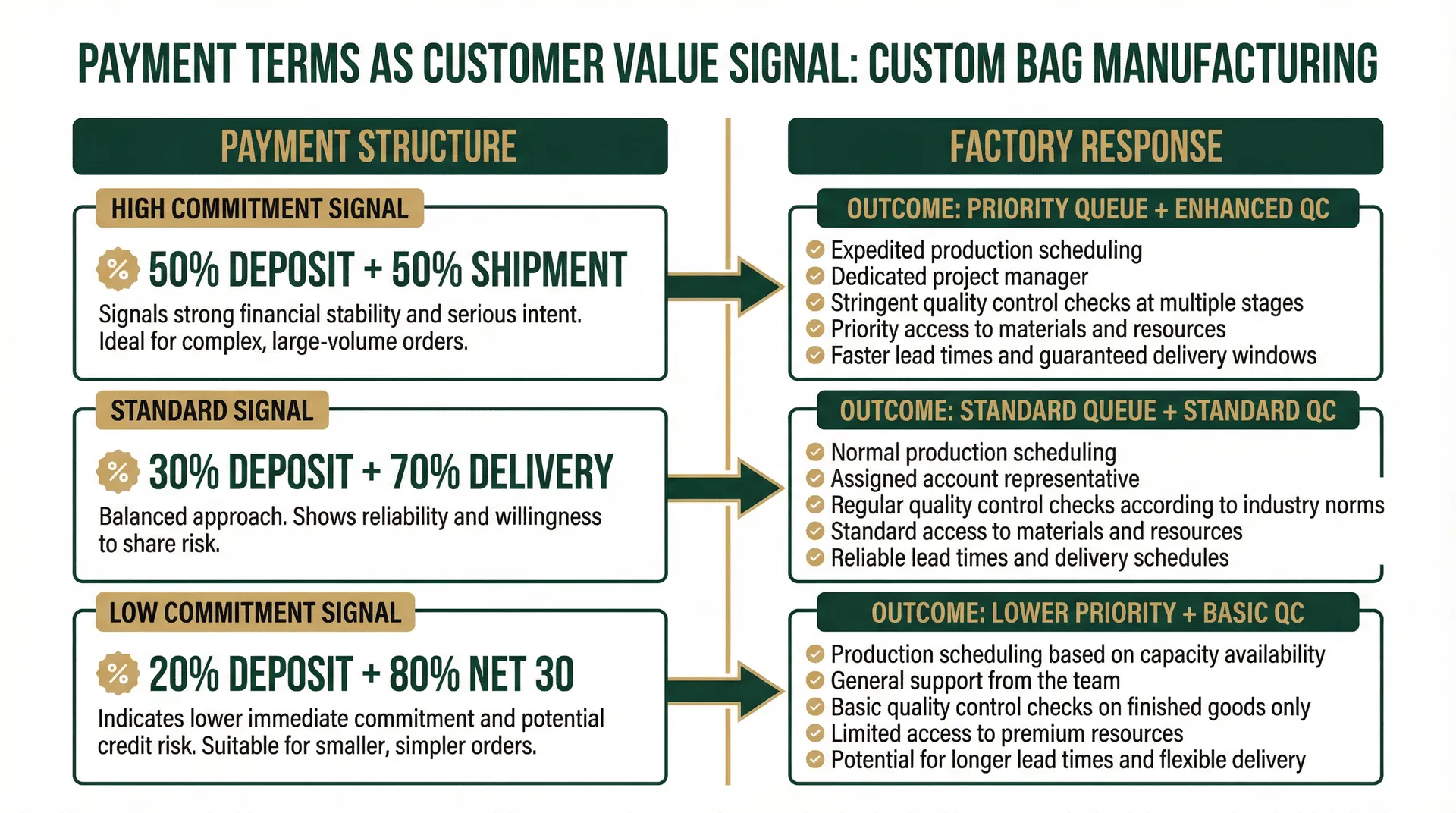

Payment terms function as a signaling mechanism within the factory's internal prioritisation system. The structure of payment—not just the timing—communicates information about the buyer that influences how the factory allocates resources, schedules production, and assigns quality control attention. A buyer who negotiates a 30/70 split with final payment contingent on delivery inspection is sending a different signal than a buyer who pays 50% upon order confirmation and 50% upon shipment. The factory receives both signals and responds accordingly, though this response is rarely made explicit.

The signal interpretation works as follows. A buyer who requires extended payment terms or back-loaded payment structures is, from the factory's perspective, demonstrating one or more of the following characteristics: cash constraints that may indicate business instability, lack of commitment to the relationship beyond the immediate transaction, or a transactional orientation that prioritises short-term leverage over long-term partnership. None of these characteristics are necessarily negative in isolation, but they inform how the factory positions that buyer within their customer portfolio.

Factories operate with finite capacity and must make allocation decisions constantly. When production schedules tighten, when quality control resources are stretched, when raw material availability becomes constrained, the factory must decide which orders receive priority attention. These decisions are not made arbitrarily. They are made based on an internal assessment of customer value, and payment behaviour is one of the most visible inputs to that assessment.

Payment terms as a customer value signal affecting production queue position

In practice, this is often where customization process decisions start to be misjudged. A procurement team negotiates what they consider favourable payment terms—perhaps a 30% deposit with 70% due thirty days after delivery—and assumes this arrangement affects only their cash position. What they do not see is that the factory has categorised them as a lower-priority customer based on this payment structure. The order will be fulfilled, but it will not receive the same attention as orders from customers who pay more upfront or who have established a pattern of reliable, prompt payment.

The manifestation of this priority differential is subtle but consequential. Lower-priority orders are more likely to experience production delays when the factory faces capacity constraints. They are more likely to be scheduled during periods when the factory's best production teams are occupied with higher-priority work. They are more likely to receive standard quality control attention rather than enhanced inspection. None of these outcomes are explicitly communicated to the buyer, and none of them would be acknowledged if asked directly. But they are real, and they affect the quality and timing of the delivered product.

The quality control dimension deserves particular attention because it is the least visible to buyers. Factories allocate their most experienced quality inspectors to orders from customers who represent the highest value and lowest risk. These inspectors catch issues earlier in the production process, intervene more proactively when problems emerge, and apply tighter tolerances when evaluating finished goods. Orders from lower-priority customers receive competent but less intensive quality attention. The difference may be marginal on any single order, but it compounds over time and across multiple production runs.

This dynamic creates a feedback loop that many buyers never recognise. A buyer who negotiates aggressive payment terms receives slightly lower priority treatment, which may result in slightly more quality issues or slightly longer lead times. The buyer interprets these outcomes as supplier performance problems and responds by maintaining or tightening their payment terms as a protective measure. The supplier interprets the continued aggressive terms as confirmation that the buyer is transactional and high-risk, reinforcing the lower-priority categorisation. Both parties are acting rationally within their own frame, but the relationship deteriorates rather than improves.

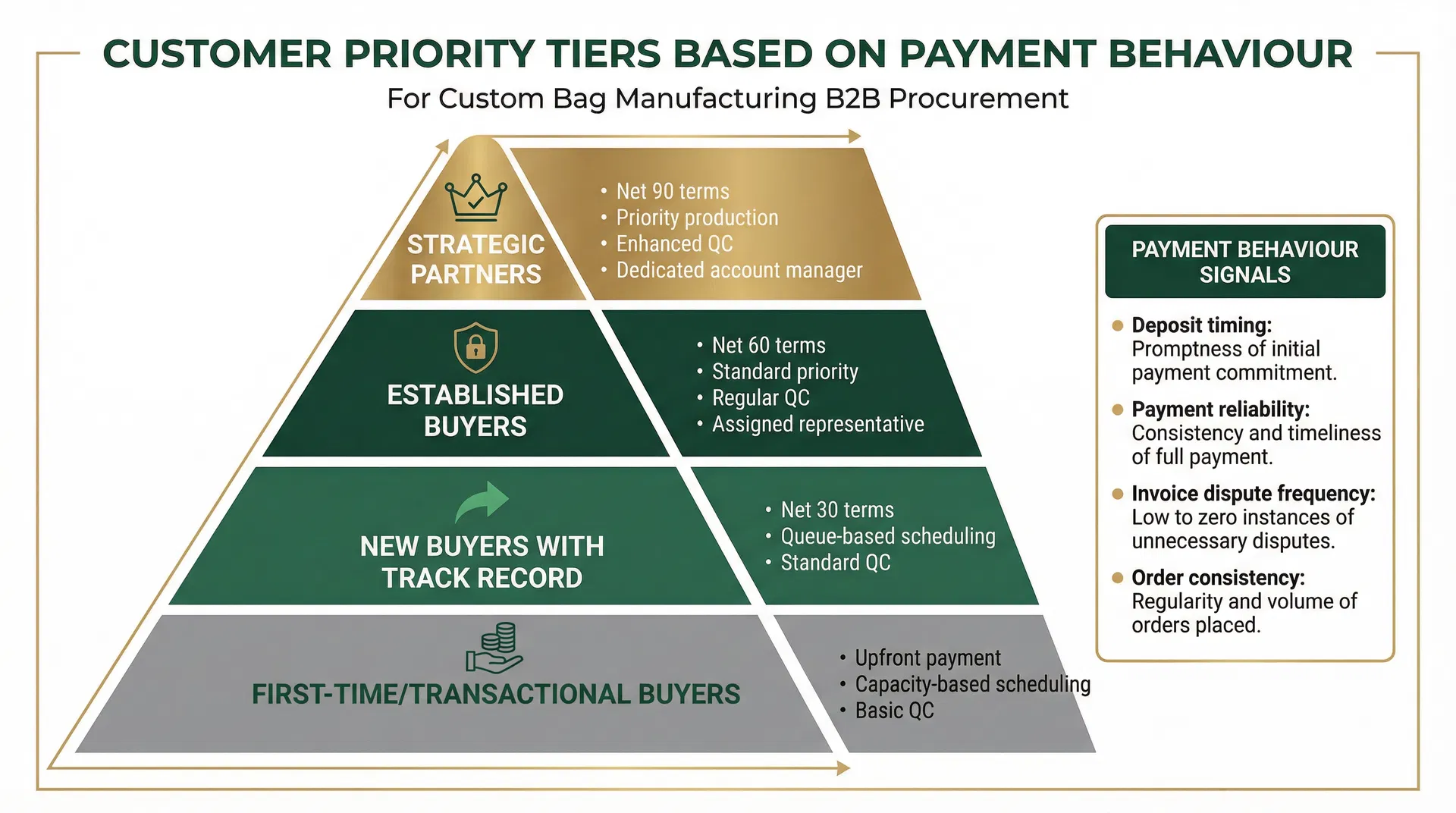

The alternative approach requires understanding payment terms as a relationship investment rather than purely a financial optimisation. Buyers who pay deposits promptly, who structure payments to reduce supplier risk, and who build a track record of reliable payment behaviour are investing in their position within the factory's customer hierarchy. This investment yields returns in the form of production priority, quality attention, and flexibility when problems arise.

Customer priority tiers based on payment behaviour and relationship signals

For organisations navigating the complete customization process for custom bags, this understanding reshapes how payment negotiations should be approached. The goal is not to extract the most favourable terms possible, but to structure terms that position the organisation appropriately within the supplier's customer portfolio. For a first order with a new supplier, this may mean accepting tighter payment terms than the buyer would prefer, with the understanding that these terms can be renegotiated as the relationship develops.

The timing of payment also carries signal value beyond the structure. A buyer who pays deposits within days of invoice receipt signals operational efficiency and financial stability. A buyer who consistently pays at the last possible moment signals either cash constraints or a transactional orientation. Factories track these patterns and adjust their internal customer ratings accordingly. The buyer may never see this rating, but they experience its effects in the form of production scheduling, communication responsiveness, and flexibility on specification changes.

There is also a category of payment behaviour that sends particularly negative signals: payment disputes. Buyers who regularly challenge invoices, request credits, or delay payment pending resolution of minor issues are flagged as high-maintenance customers. The factory's response is to build risk buffers into future dealings with that customer—higher prices, longer lead times, stricter terms, and lower priority in the production queue. The buyer may believe they are protecting their interests through rigorous invoice review, but they are simultaneously eroding their position within the supplier's priority system.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that payment terms should be evaluated not just for their cash flow impact but for their signaling impact. A payment structure that preserves working capital but signals low commitment may cost more in delayed production, quality issues, and reduced flexibility than a structure that requires earlier payment but establishes the buyer as a priority customer. This calculation is rarely made explicit in procurement training or supplier negotiation frameworks, but it is central to how factories actually operate.

For UK organisations sourcing custom promotional bags, this dynamic is particularly relevant because many buyers are placing relatively small orders in the context of the factory's total capacity. A factory producing millions of bags annually will naturally prioritise customers who represent significant, reliable volume over customers who place occasional orders with aggressive payment terms. The small buyer cannot change their volume position, but they can influence their priority position through payment behaviour that signals reliability and commitment.

The most effective approach is to treat payment terms as a negotiation that evolves with the relationship. Initial orders may require terms that favour the supplier, establishing credibility and demonstrating reliability. As the relationship develops and the buyer builds a track record of prompt payment and professional communication, terms can be renegotiated to reflect the reduced risk the buyer now represents. This progression mirrors how the factory's internal customer rating evolves, and it positions the buyer for priority treatment as the relationship matures.

There is a further consideration that experienced procurement professionals factor into their planning: the visibility of payment behaviour across the supplier's organisation. In smaller factories, payment patterns are known throughout the operation. The production manager knows which customers pay reliably and which require chasing. The quality control supervisor knows which orders come from customers who will dispute minor issues and which come from customers who accept reasonable variation. This knowledge influences behaviour at every level, not just in the commercial relationship.

The underlying principle is that payment terms are not a standalone commercial arrangement. They are one input to a complex system of signals that factories use to categorise customers and allocate resources. Buyers who understand this system can use payment behaviour strategically to improve their position within the factory's priority hierarchy. Those who treat payment terms purely as a cash flow optimisation exercise may find themselves consistently receiving lower-priority treatment without understanding why.

For organisations placing custom bag orders, the practical takeaway is to evaluate payment terms in the context of the relationship they are trying to build, not just the cash flow they are trying to manage. A payment structure that signals commitment and reliability may deliver more value through improved production priority and quality attention than the working capital benefit of more aggressive terms. The calculation is not always straightforward, but it should always be made explicitly rather than defaulting to the assumption that tighter terms are inherently better for the buyer.

The gap between how buyers think about payment terms and how factories interpret them is one of the structural misalignments that creates friction in custom bag procurement. Closing this gap requires buyers to recognise that every payment decision sends a signal, and that the factory is receiving and acting on those signals whether the buyer intends them or not. Strategic payment behaviour is not about paying more than necessary—it is about paying in ways that communicate the right message about the buyer's value and reliability as a customer.