There is a particular category of quality dispute that surfaces with predictable regularity in custom bag production, and it rarely has anything to do with actual production quality. The complaint typically arrives after delivery: the bags look different from the approved sample. The Pantone reference was specified correctly. The factory matched the colour within acceptable tolerances. The sample was approved. Yet the delivered bags, viewed in the client's showroom or at an outdoor event, appear noticeably different from what was expected.

In practice, this is where customization process decisions around colour specification begin to unravel—not because anyone made an error, but because the specification itself was incomplete in ways that neither party fully recognised at the time of approval.

The fundamental issue is that Pantone codes function as colour targets, not as complete colour specifications. A Pantone reference tells the dye house which colour to aim for. It does not specify the substrate on which that colour will be reproduced, the lighting conditions under which the match will be evaluated, or the acceptable variance from the target. These three variables—substrate, lighting, and tolerance—determine whether a correctly-matched colour will appear consistent across different viewing environments. When any of these variables changes between sample approval and final use, the colour can appear different even though the production was technically correct.

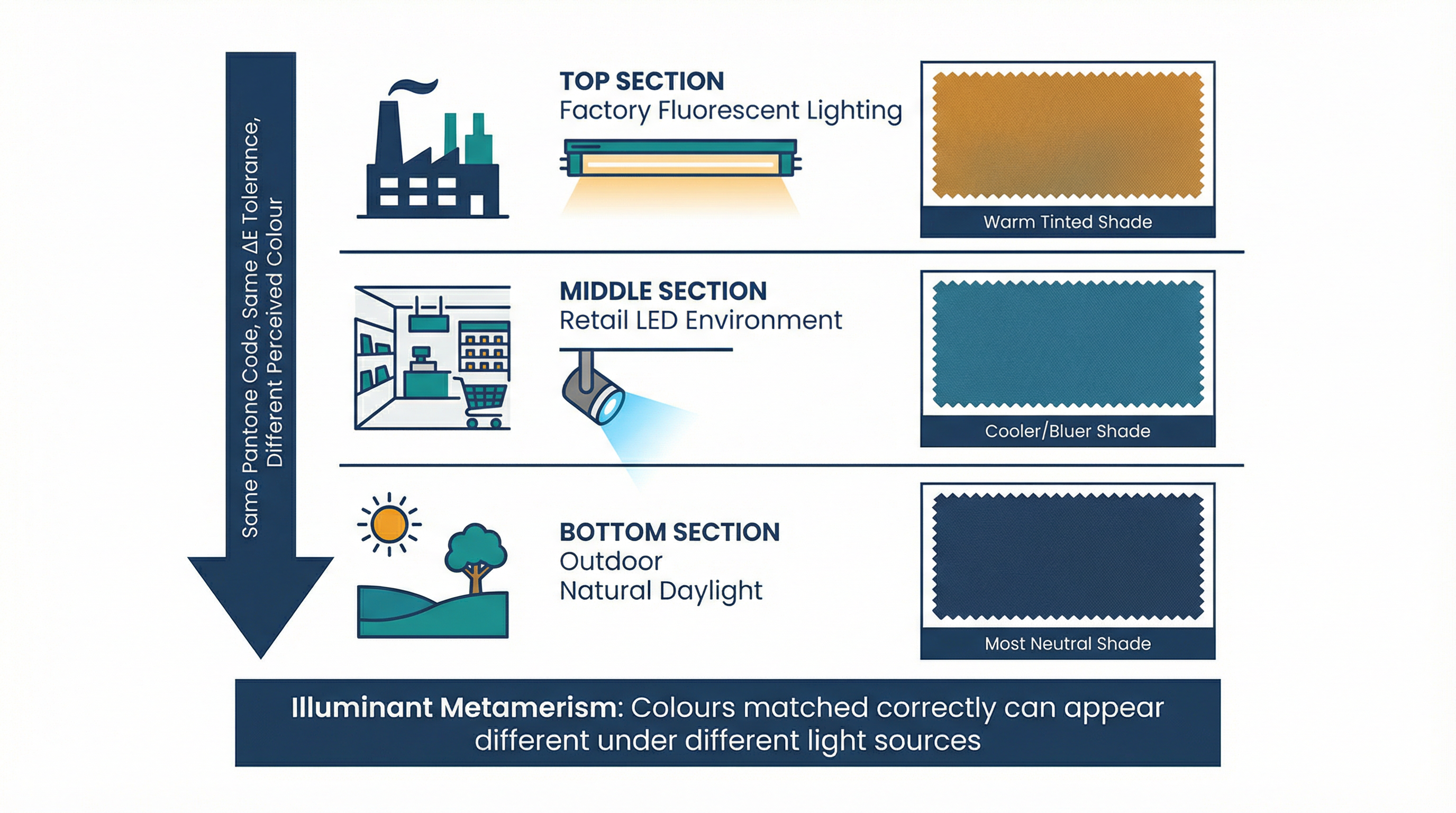

How viewing conditions affect perceived colour: The same Pantone-matched fabric can appear different under factory fluorescent lighting, retail LED lighting, and natural daylight due to illuminant metamerism.

How viewing conditions affect perceived colour: The same Pantone-matched fabric can appear different under factory fluorescent lighting, retail LED lighting, and natural daylight due to illuminant metamerism.

The substrate effect is the first variable that specifications typically fail to capture. The same Pantone colour, correctly matched, will appear different on cotton canvas versus recycled polyester versus non-woven polypropylene. This is not a production defect—it is physics. Different materials reflect light differently, and the same dye formulation produces different visual results on different substrates. When a buyer approves a sample on one fabric type and the production uses a different fabric—even a different batch of the same fabric type—the colour can shift perceptibly. The Pantone code was matched correctly. The production was executed correctly. The colour simply looks different because the substrate changed.

The lighting variable is where most disputes originate, and it is almost never addressed in specifications. Colour perception depends on three factors: the object, the observer, and the light source. Change any one of these, and the perceived colour changes. This phenomenon—illuminant metamerism—means that two colours that appear identical under one lighting condition can appear noticeably different under another. A sample approved under the factory's fluorescent lighting may look distinctly different under the LED lighting in a retail environment or the natural daylight at an outdoor corporate event. The sample and the production batch may be an exact match when measured with a spectrophotometer, yet they appear different to the human eye because the lighting changed.

The tolerance variable is the most technically precise yet least commonly specified element of colour matching. The industry measures colour difference using Delta E (ΔE), a numerical value representing the distance between two colours in three-dimensional colour space. A ΔE below 1.0 is imperceptible to the human eye. A ΔE between 1.0 and 2.0 is noticeable only under controlled lighting. A ΔE between 2.0 and 3.0 is visible but generally considered acceptable in textile production. A ΔE above 3.0 is clearly noticeable and typically falls outside acceptable standards.

The critical point is that most colour specifications do not include a ΔE tolerance. When a buyer specifies "Pantone 485 C" without indicating an acceptable ΔE range, the supplier applies their own interpretation of acceptable variance. One supplier may target ΔE 0.75. Another may consider ΔE 2.5 acceptable. Both are technically "matching" the Pantone reference. Both are operating within industry norms. Yet the visual difference between ΔE 0.75 and ΔE 2.5 is noticeable to anyone comparing the two.

The practical consequence is that two production batches, both correctly matched to the same Pantone code, can have a ΔE of 3.0 between them. Each batch individually matches the Pantone target within acceptable tolerances. But when placed side by side—as happens when bags from different production runs are used at the same event—the colour difference is visible. This is not a quality failure. It is the mathematical reality of tolerance stacking that specifications without explicit ΔE requirements cannot prevent.

For organisations managing custom bag orders where brand colour consistency matters, the specification needs to extend beyond the Pantone code. The substrate must be specified and confirmed before sample production. The lighting conditions for evaluation should be agreed—ideally matching the conditions where the bags will actually be used. The acceptable ΔE tolerance should be stated explicitly, with the understanding that tighter tolerances may require additional production time and cost.

Understanding how these colour variables interact with the broader stages of bringing a custom bag from concept to delivery helps procurement teams set realistic expectations and avoid disputes that arise from physics rather than production errors. Recognising how colour specification fits within the complete customization process allows organisations to address these variables before production begins, rather than discovering them after delivery.

The bags that look different in the showroom are not necessarily evidence of poor production. They may be evidence of a specification that captured the colour target but not the conditions under which that target would be evaluated. The distinction matters—both for resolving the immediate dispute and for preventing the same issue on future orders.

The metamerism issue becomes particularly acute when custom bags incorporate multiple materials or printing techniques. A corporate tote bag might combine a dyed fabric body with a screen-printed logo and a woven label. Each of these elements responds differently to the same Pantone specification. The fabric absorbs dye. The screen print sits on the surface. The woven label uses thread that reflects light differently again. Even when all three elements are matched to the same Pantone code within acceptable tolerances, they can appear as three slightly different shades under certain lighting conditions. The brand manager who approved each element separately may be surprised to see them appear inconsistent when combined on the finished product.

This is not a theoretical concern. It manifests regularly in orders where the client's brand guidelines specify a single Pantone reference for all applications without acknowledging that different substrates and production methods produce different visual results. The factory has done nothing wrong. The colour matching was correct. The specification simply assumed that Pantone codes produce identical results across all materials and methods, which they do not.

The timing of colour evaluation adds another layer of complexity. Dyed fabrics can shift slightly during storage, particularly if exposed to light or humidity variations. A sample approved immediately after dyeing may appear marginally different from production fabric that has been warehoused for several weeks before cutting. The shift is typically within acceptable ΔE tolerances, but it contributes to the cumulative variance that can make delivered bags look different from approved samples.

Temperature during evaluation also affects colour perception, though this is rarely considered in specifications. Fabric viewed at room temperature in an air-conditioned showroom may appear slightly different from the same fabric viewed outdoors on a warm day. The difference is subtle but measurable, and it compounds with other variables to create the perception that the colour has shifted when in fact the viewing conditions have changed.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that colour approval should replicate, as closely as possible, the conditions under which the final product will be used. If the bags will be displayed at outdoor events, the sample should be evaluated in natural daylight, not under factory fluorescents. If the bags will be used in a retail environment with specific LED lighting, that lighting condition should be replicated during approval. If the bags will be photographed for marketing materials, the photography lighting should be considered during colour selection.

Some organisations address this by requesting samples evaluated under multiple light sources—a practice known as multi-illuminant colour matching. The sample is viewed under daylight, under incandescent light, and under fluorescent light. If the colour appears consistent across all three conditions, the risk of metamerism-related disputes is significantly reduced. This approach adds time and cost to the sampling process, but it prevents the far greater cost of rejecting a production run or accepting bags that appear inconsistent with brand standards.

The ΔE tolerance specification deserves particular attention for repeat orders. When an organisation places multiple orders over time—perhaps ordering bags quarterly for ongoing campaigns—each production run is matched to the original Pantone target. But if each run is allowed a ΔE tolerance of 2.0, and the runs happen to fall on opposite sides of the target, two consecutive batches could have a ΔE of 4.0 between them while both technically meeting specification. For organisations that need batch-to-batch consistency, the specification should include not only the tolerance from the Pantone target but also the maximum acceptable variance between production runs.

The colour disputes that arise from viewing condition variables are fundamentally different from disputes arising from production errors. A production error—wrong dye formulation, incorrect colour reference, contaminated dye bath—produces a colour that does not match the specification under any conditions. A viewing condition variance produces a colour that matches the specification under some conditions but appears different under others. The resolution approaches are entirely different. Production errors require rework or replacement. Viewing condition variances require specification refinement for future orders and, often, education about why the current production is technically correct even though it appears different from expectations.

For organisations placing their first custom bag orders, the colour specification conversation should happen early in the process—before sampling begins. The questions to address include: What substrate will be used, and has the Pantone colour been validated on that specific material? Under what lighting conditions will the bags primarily be used? What ΔE tolerance is acceptable for this application? Will multiple production runs need to match each other, and if so, what batch-to-batch variance is acceptable?

These questions may seem technical for a marketing or procurement team to address, but they prevent disputes that are far more difficult to resolve after production is complete. A supplier who understands the end-use conditions can advise on colour selection, recommend appropriate tolerances, and flag potential metamerism risks before they become delivery disputes.

The bags that look different in the showroom are often the result of specifications that captured the colour but not the context. Addressing that context before production begins is the most reliable way to ensure that the delivered product matches expectations—not just the Pantone code, but the actual visual experience the organisation intended.