There is a recurring pattern in custom bag procurement that catches even experienced buyers off guard. An organisation identifies a supplier, confirms specifications, receives a quotation with a stated minimum order quantity, and proceeds to place an order at exactly that threshold. The expectation is straightforward: meet the minimum, and production begins. What actually happens is often more complicated, and the complication stems from a structural gap between what the factory quotes and what the supply chain requires.

The minimum order quantity stated in a quotation represents the factory's internal threshold—the point at which their own labour allocation, machine setup, and margin calculations become viable. It does not represent the thresholds of every upstream supplier involved in producing that specific bag. This distinction matters because custom bag production is not a single-entity operation. It is a coordinated effort across multiple tiers: fabric mills, trim suppliers, hardware manufacturers, zipper producers, label printers, and packaging vendors. Each of these entities has their own minimum order requirements, and those requirements are often invisible to the buyer until the order encounters them.

Consider a practical scenario. A procurement team orders 500 custom promotional tote bags with a specific Pantone-matched fabric, custom-dyed webbing handles, and a proprietary metal logo plate. The factory quotes an MOQ of 500 pieces and the buyer commits. What the buyer does not see is that the fabric mill requires a minimum of 800 metres to run that specific colour, the webbing supplier requires 2,000 metres minimum for custom dyeing, and the hardware supplier requires 3,000 pieces minimum for the logo plate mould. The factory's quoted MOQ of 500 bags may require materials sufficient for 1,200 bags, hardware for 3,000 bags, and webbing for 1,500 bags. The buyer has met the factory's threshold but has not met the supply chain's effective threshold.

This is where the customization process begins to diverge from expectations. The factory, having accepted the order in good faith, now faces a procurement problem. They can absorb the excess material cost and carry dead stock, negotiate with suppliers for exceptions, substitute components with stock alternatives, or return to the buyer with revised terms. None of these outcomes were visible at the quotation stage, and all of them introduce friction that the buyer did not anticipate.

The challenge is compounded by the way quotations are typically structured. A factory quotes based on the assumption that specifications will be finalised and that procurement will proceed smoothly. They do not typically itemise the upstream MOQ constraints for every component because doing so would make quotations unwieldy and would require supplier confirmations that slow down the sales process. The result is a quoted MOQ that functions as a starting point rather than a guarantee.

Comparison of factory-quoted minimum order quantity versus the effective minimum required by upstream suppliers for custom components

Comparison of factory-quoted minimum order quantity versus the effective minimum required by upstream suppliers for custom components

In practice, this is often where customization process decisions start to be misjudged. Buyers interpret the quoted MOQ as a fixed threshold that, once crossed, unlocks production. The reality is that the quoted MOQ unlocks the factory's willingness to produce, but production itself depends on whether the specification can be sourced at that volume. For standard specifications—stock fabrics, standard hardware, common zipper configurations—the quoted MOQ and effective MOQ are often aligned. For custom specifications, they frequently diverge.

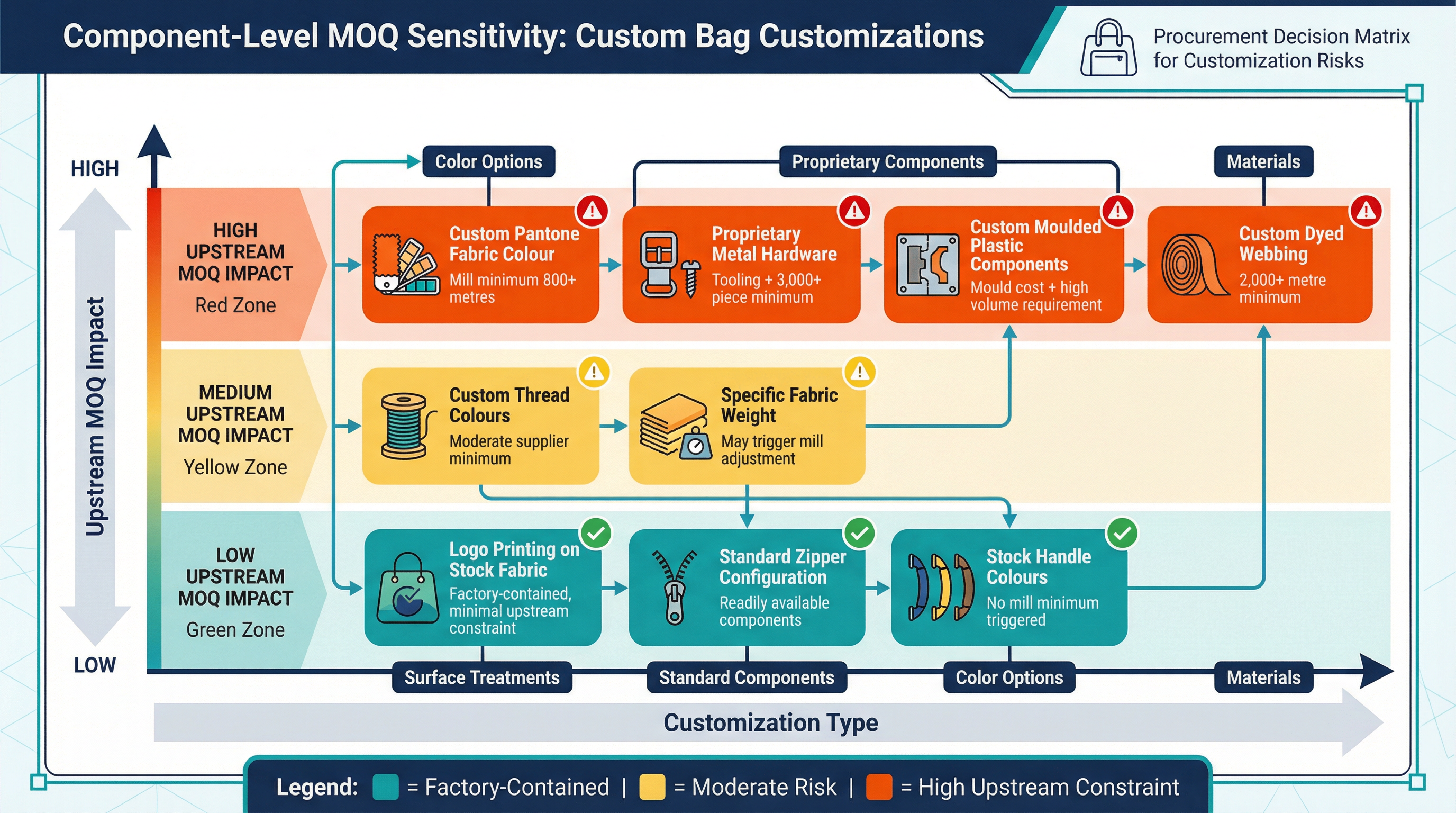

The divergence is not uniform across all customizations. Some elements are MOQ-sensitive while others are not. Logo printing on stock fabric, for instance, typically adds minimal upstream constraint because the fabric already exists and the printing setup is amortised across the order. Custom fabric colours, by contrast, trigger mill minimums that may exceed the bag order by a factor of two or three. Custom hardware—particularly proprietary metal fittings or moulded plastic components—often carries the highest upstream MOQ because tooling costs must be justified against volume.

Understanding which customizations trigger upstream constraints allows procurement teams to structure orders more strategically. A buyer who wants 500 bags with a custom Pantone fabric might negotiate to use a mill-stock colour that is close to the target, avoiding the fabric MOQ constraint entirely. A buyer who insists on custom hardware might consolidate that hardware across multiple product lines or future orders to meet the supplier's threshold. These are not compromises in the negative sense; they are informed adjustments that align the order with supply chain realities.

The timing of this alignment matters. If the gap between quoted MOQ and effective MOQ is discovered after the order is placed, the buyer faces a choice between accepting revised terms, accepting substitutions, or cancelling. If the gap is discovered during specification development, the buyer can adjust the specification proactively. Recognising how minimum order requirements interact with the broader stages of custom bag production helps organisations anticipate these constraints rather than react to them.

There is also a temporal dimension to the effective MOQ that is often overlooked. Upstream suppliers do not hold capacity indefinitely. A fabric mill that can produce 800 metres of a custom colour in February may have a 2,000-metre minimum in June because their production schedule has shifted. A hardware supplier that accepts 1,000-piece orders during slow periods may require 5,000 pieces during peak season. The effective MOQ is not static; it fluctuates with supplier capacity, raw material availability, and market demand.

For UK organisations sourcing custom bags, this dynamic is particularly relevant because many upstream suppliers are located in different time zones and operate on different production calendars. A specification confirmed in January may encounter different upstream constraints when procurement actually occurs in March. The quoted MOQ from the factory remains the same, but the effective MOQ from the supply chain has shifted.

The practical implication is that meeting the quoted MOQ is necessary but not sufficient. It is the entry point to a negotiation with the supply chain, not the conclusion of one. Buyers who treat the quoted MOQ as a guarantee are likely to encounter friction when upstream constraints emerge. Buyers who treat the quoted MOQ as a starting point—and who probe for upstream constraints during specification development—are better positioned to structure orders that proceed smoothly.

This does not mean that every order requires exhaustive supply chain mapping. For standard specifications, the quoted MOQ is usually reliable. For custom specifications, particularly those involving custom colours, custom hardware, or proprietary components, the gap between quoted and effective MOQ is worth investigating before commitment. A simple question during the quotation process—"Are there any upstream supplier minimums that exceed your quoted MOQ for this specification?"—can surface constraints that would otherwise emerge as surprises.

The underlying principle is that custom bag production is a networked process, not a linear one. The factory is a node in that network, but they are not the only node. Meeting their threshold does not automatically satisfy the thresholds of every other node. Recognising this structure allows procurement teams to navigate the customization process with greater precision, avoiding the friction that arises when quoted minimums and effective minimums diverge.

Component-level MOQ sensitivity: which customizations trigger upstream constraints and which remain factory-contained

Component-level MOQ sensitivity: which customizations trigger upstream constraints and which remain factory-contained

The visibility gap extends beyond the initial quotation. Even after an order is placed, the effective MOQ can shift if specifications change. A buyer who adds a custom zipper pull after approval has introduced a new upstream constraint that may not align with the original order quantity. A buyer who changes the fabric weight has potentially triggered a new mill minimum. Each specification adjustment is not merely a design decision; it is a supply chain decision that may alter the effective MOQ.

This is why specification freezes matter in ways that are not always obvious. A frozen specification is not just a design lock; it is a supply chain lock. It allows the factory to confirm upstream availability and pricing at the specified volume. When specifications change after that confirmation, the supply chain must be re-queried, and the effective MOQ may have shifted in the interim.

For organisations placing orders at or near the quoted MOQ, this dynamic creates particular vulnerability. An order of 5,000 pieces has buffer capacity to absorb upstream minimum variations. An order of 500 pieces—exactly at the quoted threshold—has no buffer. Any upstream constraint that exceeds the order quantity becomes a blocking issue rather than an absorption issue.

The strategic response is not to avoid custom specifications but to understand which specifications carry upstream MOQ risk and to structure orders accordingly. Some organisations consolidate multiple product lines into single upstream orders, meeting fabric minimums across bags, pouches, and accessories rather than per-product. Others phase their orders, committing to larger initial runs that meet upstream thresholds and then drawing down from stock for subsequent needs.

There is also value in understanding the factory's own relationship with their suppliers. A factory with long-standing supplier relationships may have negotiated lower minimums or may carry buffer stock of common custom components. A factory that sources opportunistically may face higher upstream thresholds because they lack the volume history to negotiate exceptions. The quoted MOQ is the same in both cases, but the effective MOQ differs based on the factory's supply chain position.

For UK buyers sourcing custom reusable bags, the practical takeaway is that the quoted MOQ is a starting point for conversation, not a finish line. It represents the factory's internal economics, not the supply chain's collective requirements. Understanding this distinction allows procurement teams to ask better questions during specification development, to structure orders that align with upstream realities, and to avoid the friction that arises when quoted minimums prove insufficient for actual production.

The gap between quoted and effective MOQ is not a failure of transparency; it is a structural feature of networked manufacturing. Factories quote based on their own thresholds because that is what they control. Upstream thresholds emerge during procurement because that is when they are confirmed. Buyers who recognise this sequence can navigate it strategically. Those who assume the quoted MOQ is the effective MOQ are likely to encounter surprises that delay timelines and complicate relationships.