The request arrives in a familiar form: "Can we just change the handle colour from navy to black? Everything else stays the same." The procurement team forwards it to the supplier, expecting perhaps a two-day adjustment to the timeline. What they receive instead is a revised delivery date that adds three weeks to the schedule. The internal reaction is predictable—frustration, accusations of supplier inflexibility, and a lingering suspicion that the factory is using the change as leverage for additional charges.

This pattern repeats across corporate gifting programmes, promotional campaigns, and branded merchandise orders with remarkable consistency. The disconnect between buyer expectation and supplier response isn't a communication failure or a negotiation tactic. It reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how production scheduling works in custom bag manufacturing, and why design changes—even seemingly minor ones—don't simply add time to an existing timeline but reset the queue entirely.

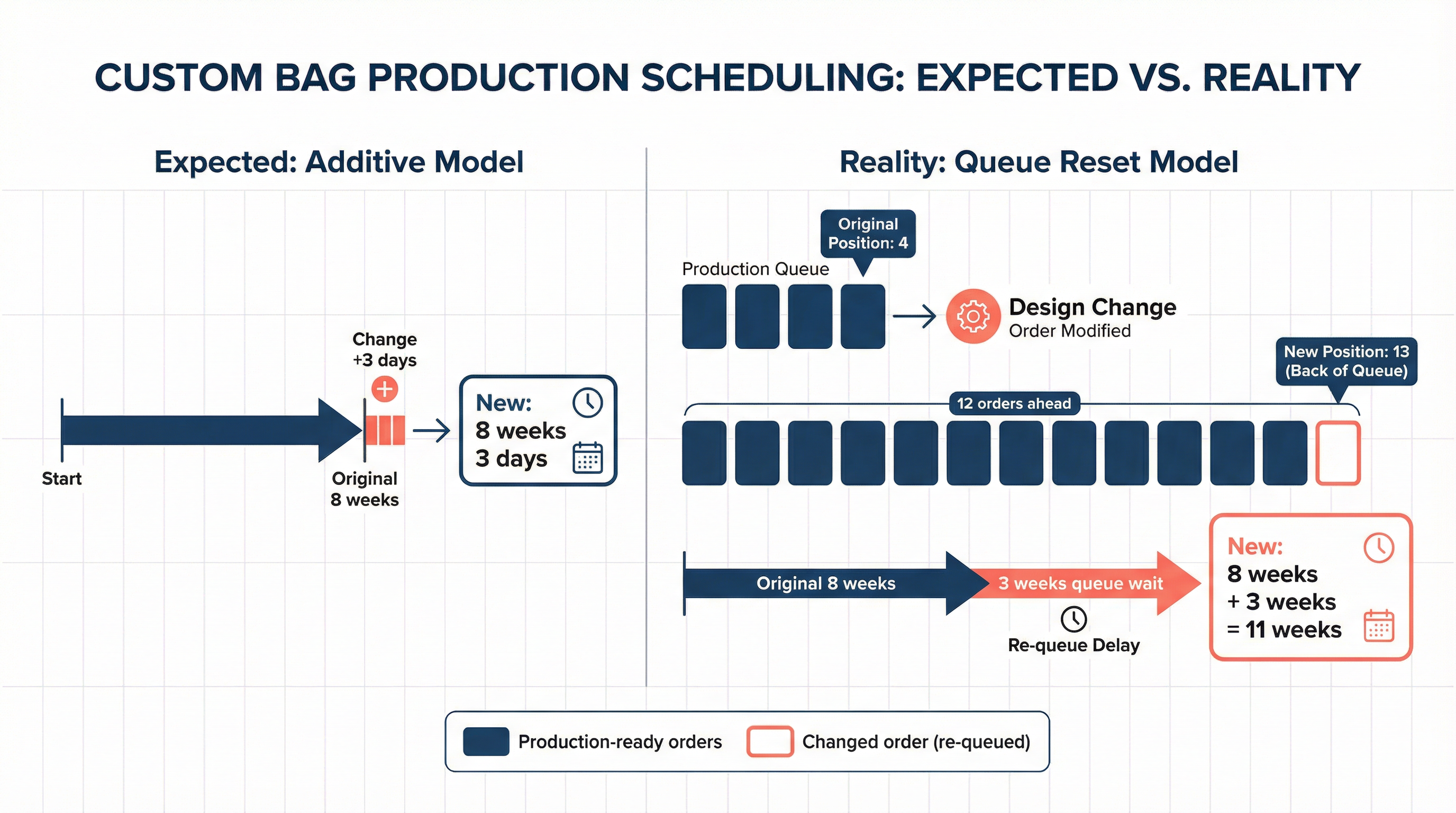

The mental model most procurement teams carry is additive: original timeline plus change processing time equals new timeline. If the original delivery was eight weeks and the change takes three days to implement, the new delivery should be eight weeks and three days. This arithmetic makes intuitive sense but bears no relationship to how factories actually schedule production.

Production scheduling in bag manufacturing operates on a slot system. When a factory confirms a delivery date, they're not simply estimating how long the work will take—they're reserving a specific position in their production queue. That position is allocated based on the order being production-ready: approved sample, confirmed materials, finalised artwork, and all specifications locked. The factory has coordinated material procurement, allocated machine time, assigned operators, and scheduled quality control resources around that specific slot.

A design change, regardless of how minor it appears from the buyer's perspective, invalidates the production-ready status. The order is no longer what was scheduled. The factory cannot proceed with production because the specifications have changed, which means the reserved slot cannot be used for that order. But the slot doesn't sit empty—it gets reallocated to the next production-ready order in the queue.

This is where the queue reset effect emerges. The changed order doesn't simply pause and resume; it moves to the back of the line behind all orders that are currently production-ready. If the factory has twelve orders scheduled ahead, and your order was in position four, a design change doesn't move you to position four-and-a-half. It moves you to position thirteen—after all the orders that haven't changed their specifications.

The practical consequence is that a "three-day change" can easily become a three-week delay. The three days represent the actual work required to implement the change—updating patterns, sourcing different materials, revising artwork files. The remaining time is queue time: waiting for a new production slot to become available.

This dynamic is particularly acute during peak seasons. When factories are running at high capacity utilisation, the queue of production-ready orders is longer, and new slots become available less frequently. A design change submitted in September, when factories are processing Q4 orders, may face a queue that extends weeks into the future simply because every available slot is already committed to orders that haven't changed.

The situation compounds when the design change triggers upstream procurement requirements. A handle colour change from navy to black might seem trivial—both colours exist, both are standard options. But if the factory had already procured navy webbing for the original order, they now need to source black webbing. If the black webbing isn't in stock, it must be ordered from the supplier. If the supplier has minimum order quantities, the factory may need to wait until they have enough orders requiring black webbing to meet that minimum. Each of these dependencies adds queue time that has nothing to do with the actual production work.

The version control dimension adds another layer of complexity. When a design change is communicated, the factory must confirm they're working from the correct updated specification. In practice, this often requires a new sample or at minimum a revised technical pack approval. The buyer's internal stakeholders who approved the original design may need to re-approve the changed version. If those stakeholders are unavailable, travelling, or simply slow to respond, the order sits in limbo—not production-ready, not in the queue, accumulating delay that will eventually be attributed to the supplier.

What makes this particularly frustrating for procurement teams is that the delay appears disproportionate to the change. A colour substitution that takes an operator five minutes to implement at the sewing station somehow adds weeks to the delivery schedule. The explanation—queue mechanics, slot reallocation, upstream procurement, version control—sounds like bureaucratic excuse-making. But the underlying reality is that factories optimise for throughput, and throughput depends on processing production-ready orders in sequence. Orders that aren't production-ready, regardless of the reason, cannot be processed efficiently.

The strategic implication for UK businesses managing custom bag orders is that design changes should be treated as timeline resets, not timeline extensions. The question isn't "how much time does this change add?" but "where does this change put us in the queue?" Understanding this distinction transforms how procurement teams communicate with internal stakeholders about the cost of late-stage modifications.

Recognising how these scheduling dynamics interact with the broader stages of bringing a custom bag from concept to delivery helps organisations build more realistic project timelines and establish change management protocols that account for queue effects rather than assuming linear time additions.

The practical defence against queue reset delays is specification lock. Establishing a clear point in the project timeline after which design changes are not permitted—or are permitted only with explicit acknowledgment of queue reset consequences—prevents the cascading delays that result from well-intentioned "minor adjustments." This requires internal alignment: marketing, brand, and procurement must agree that the approved specification is final, and that post-approval changes carry timeline costs that may exceed the value of the change itself.

For organisations that cannot avoid late-stage changes, the mitigation strategy involves maintaining buffer time that accounts for queue effects rather than just processing time. If a project timeline assumes an eight-week production window with no margin, a design change that triggers a queue reset will inevitably miss the deadline. Building in two to three weeks of buffer specifically for queue contingencies—not just production contingencies—provides the flexibility to absorb changes without catastrophic schedule impact.

The supplier relationship dimension also matters. Factories that have long-standing relationships with buyers, and that anticipate repeat business, may be more willing to accommodate changes by holding slots or prioritising re-queued orders. This flexibility isn't free—it comes from the accumulated goodwill of consistent ordering, clear communication, and realistic expectations. Buyers who treat every order as a transactional negotiation, extracting maximum concessions on price and timeline, find that their orders receive no special consideration when changes arise.

The deeper issue is that design changes after approval represent a failure of the approval process itself. If the handle colour needed to be black, that should have been determined before sample approval. If the brand team wasn't certain about the colour, the sample should have been produced in multiple colourways for comparison. The cost of producing additional samples is trivial compared to the cost of a queue reset during production scheduling.

This perspective shifts the conversation from "why is the factory being difficult about a simple change?" to "why didn't we finalise this decision earlier?" The answer is usually that internal stakeholders weren't engaged at the right time, or that the approval process didn't require sufficient specificity, or that someone assumed changes would be easy to accommodate. These are process failures on the buyer side, not supplier failures.

The organisations that navigate custom bag production most successfully are those that treat the customization process as a series of irreversible decisions rather than a fluid negotiation. Each stage—design concept, material selection, sample approval, production scheduling—represents a commitment that becomes increasingly expensive to reverse. Understanding that design changes after scheduling don't just cost time but cost queue position transforms how teams approach the approval process and how they communicate the consequences of late-stage modifications to internal stakeholders who may not appreciate the operational realities of manufacturing.

The queue reset effect isn't a supplier tactic or an industry quirk. It's a structural characteristic of how production scheduling works when factories are managing multiple orders with finite capacity. Buyers who understand this dynamic make better decisions about when to finalise specifications, how much buffer to build into timelines, and when a proposed change is worth the queue cost it will incur. Those who don't understand it will continue to be surprised when "minor" changes produce major delays, and will continue to attribute those delays to supplier intransigence rather than scheduling mechanics.